I was born and bred in LA just like my parents and grandparents, and my entire life I thought it was the greatest place on earth. But, after the effects of the pandemic rippled through my rapidly expanding company, my wife posed the simplest of questions with the greatest of implications.

”What if?”

A studio is a home of sorts, it houses tools permanently, materials temporarily, and the constantly shifting energy of creativity eternally. Since starting my business eleven years ago, I have moved my studio a total of nine back breaking times. When one of the moves left me with a nasty case of shingles, I vowed to never move again. The final move to Northern California required seven 43-foot flatbed loads transporting twenty tons of machines, tools, and natural materials.

I began designing my studio as a machine for creativity with passive energy systems throughout. Where to plant the building was the first question. Shaded by a row of Monterey Cypress over 150 years old, I placed the building just far enough away that the sun could still spill over their towering canopies and wash the roof with light while shading the otherwise impractical black metal facade black. Positioned as close as possible to the street to minimize disruption to the soil, a larger driveway had to be cut into the land with strategic and subtle curves, it is now wide enough for a 53-foot semitruck trailer.

The skylights and windows peer out unto the countryside while embedding the work with natural light. Their careful placement allows them to draw in deep breaths of fresh air and exhale a fine mist of sawdust aided by extra wide and tall overhead doors that climb up the ceiling and provide a seamless transition from indoors to outdoors. With these monolithic doors and a large exterior concrete pad, I eliminated the interior dead space that is often devoured by forklift access and forced myself to interact with the outdoor environment every time I had to move large pieces from one side of the shop to the other.

This move alone has forced me into the rain that I used to run from in the city, causing surprising moments of delight such as watching the rain raise the grain of a freshly planed table surface, an important step in ensuring the success of a natural oil/wax finish.

Preferring to store the slabs and lumber vertically, the way they are found in nature, I pushed and pulled the ceiling while optimizing the pitch for solar panel sunbathing. The expansive roof takes gulps of rain and redirects the water into twenty thousand gallons of storage that irrigates the Walnut and fruit orchard, native plants, as well as the garden. And finally, a polished 3,000 square foot concrete pad allows for easy cleanup and rolling of tables throughout the studio.

I designed the building around the ideal machine layout, rather than the layout to the building.

One of the lessons that I was forced to learn as my collection of machines, tools, and projects grew in scale was the importance of a good layout. My first shop layout was determined by the fact that half of the roof leaked, forcing the metal shop into that space and the woodshop into the crowded, low ceiling rear with terrible access. It was like working in a ground level basement and I can vividly remember the thuds caused by repeatedly bumping freshly sanded boards into the walls and low ceiling every time they had to be rotated or flipped.

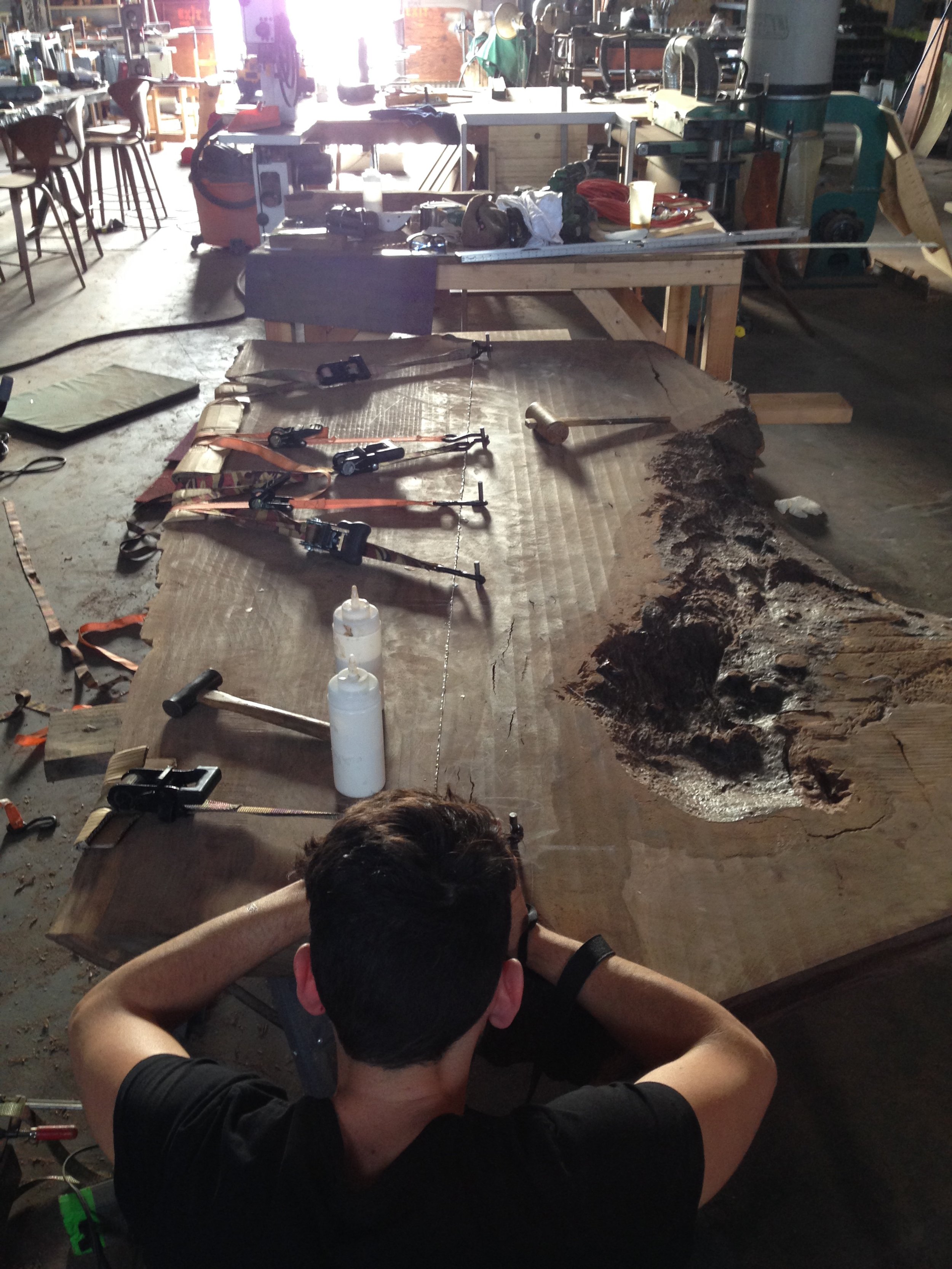

Four of the six studios that I had were shared with other woodworkers and I quickly learned the importance of dust collection, shared circulation space, and communication. Together we forged towards South LA where a gorgeous, run down 3,500sqft metal building could be split among the three of us. The new studio provided ample space to expand the scale of projects, create a shared machine area and private workspaces, and share knowledge as well as the weight of heavy projects. That was the hottest summer of my life! We worked in sopping wet headbands, baking in a metal building with no insulation, and experienced the effects of the oven, baking on the inside. A few months later, rains came pouring down and we quickly learned the building was not watertight when a small creek began flowing through the space. All of this combined with a porta potty that was our permanent bathroom, and we were forced to move again just eight months later.

Past Studios Throughout the Years (2012-2020)

Being self-taught meant I was always in a position of learning, often the hard way.

Being born somewhere between the Baby Boomers and Gen Z, I was raised in an environment of unpaid internships, being the new guy who was often targeted by the veterans’ jokes and being dismissed by the “old school” folks at lumbermills and metal yards that I often sought to impress. I mirrored this attitude in my studio, often to the quiet frustration of my employees. It wasn’t until an employee who had been with me for four years blew up on me that I began to understand the error in my ways.

Now, I work alone. I bare the burden of my own mistakes, enjoy the solitude of natural surroundings, a rotating playlist, and a deeper connection to the materials and work. I truly feel in my element, an older and much wiser version of my younger self. As I continue to develop my skills and tools, continue to explore the materials and craft with eagerness and humility, I will never forget what it took to get here and what it will take to go to the next chapter.

My next studio was further south in South LA and the space was incredible, watertight and freshly renovated with a new electrical panel. It even came with a loading dock which seemed ideal at the time, but we quickly learned that not having ground floor access made it incredibly difficult to unload large slabs, machines, and finished pieces. My solution was to hire a tow truck to load our neighbor’s forklift onto and then back it up to the loading dock and drive it into the shop. My portion of the space was surrounded by the most wall space in the back of the studio, but also had an odd ten-inch step running through the middle of it making it challenging to place three-ton machinery into position; this ultimately led my jointer to tip backwards onto its motor, surprisingly leaving just a scratch in the 100-year-old iron housing.

More space led to more and larger projects, and with no easy access to a forklift or clear aisles for it snake through, I sought a few strong employees to help with lifting, sanding, and joinery. I paid as much as I could, often forgoing my own paycheck to fulfill my obligations towards my employees and landlord. As my bank account grew, I continued to seek ways to reinvest the money. Health insurance, more modern and efficient machinery, workers compensation, sick pay, and better hand and power tools topped my list. As the benefits grew, so did the number of employees, both good and bad. The truth is, I learned from them both, and continued to learn about what it meant to be an employer and why I wasn’t such a good one. Despite encouraging employees to expand their skillset, take their time, and seek perfection just as I do in my own practice, I often went about communicating it in the wrong way.